WTF Happened: Bitcoin Violence And Elon Departs

On attacks with $5 wrenches and on Social Security

Measuring Financial Assets

Until about 2020, the valuation of essentially every financial asset was easily explainable. That didn’t mean the valuation was correct, certainly: for instance, the stock market essentially is an endless series of arguments over the “right” valuation for each individual stock. And those arguments change endlessly in turn, updating constantly as new information is understood.

Certainly, investors were not perfect. There were panics and bubbles, even if those bubbles were less ridiculous than some might believe1. But overall, there were formulae for what these assets were worth. A stock, in theory, should be worth the cumulative amount of free cash flow2 generated by the corporation, with future cash flows discounted (a dollar in 2035 is not worth a dollar today). A piece of real estate was worth its rental income, less expenses, with, again, future flows discounted back. And there were shortcuts — price-to-earnings ratio for stocks, ‘cap rate’3 for real estate — that underpinned and simplified the fundamental, financial, discussion.

Similar analyses held true in commodities (crude oil prices are highly sensitive to global economic growth, for instance) or currencies (trade flows and inflation matter here). With one exception that we’ll get to, financial assets were, broadly speaking, not just explainable but measurable. Different investors might have different measurements, certainly, but they were all trying to get to the same place.

How Do You Value Cryptocurrency?

The rise of cryptocurrency last decade upended all that. From the jump, traditional investors pretty much scorned Bitcoin, at least in part because there was no way to measure its value. Bitcoin had no cash flows like a business; it paid no interest like a bond; and it didn’t even really match up to currency valuation models. Its value was essentially a bet on everyone else believing it had value, which sounds at bet like a circular argument and at worst simply a Ponzi scheme.

There was one asset which operated on a similar principle: gold. But gold had about 5,000 years’ worth of history, during which time human beings across the globe had come to an agreement that the metal was prima facie valuable. And even with that massive head start, gold still retained its skeptics among the investor class. As Warren Buffett put it:

[Gold] gets dug out of the ground in Africa, or someplace. Then we melt it down, dig another hole, bury it again and pay people to stand around guarding it. It has no utility. Anyone watching from Mars would be scratching their head.

Bitcoin didn’t have that history, of course: the white paper by the pseudonymous Satoshi Nakamoto that established the Bitcoin protocol was released in October 2008. And without that history, there didn’t seem to be much in the way of utility — and, to many, there still doesn’t.

Indeed, the question skeptics repeatedly ask of Bitcoin, and crypto more broadly, is: “What is the use case?” In other words, what does crypto add to the global financial system? After all, much of crypto is simply replicating the existing financial system. Bitcoin and Ethereum as currencies. DeFi (decentralized finance) applications mimic exchanges and markets that already exist. The rise of stablecoins provides what are essentially tokenized dollars that can be transferred electronically — but we already have tokenized dollars. They’re called dollars: the overwhelming majority of American wealth consists of entries in digital spreadsheets, not in paper money.

Bitcoin proponents would occasionally nod to cross-border flows, or the value of citizens in unstable regimes like Venezuela being able to avoid the punishing inflation in their economies. But even that case didn’t necessarily argue for the Bitcoin price to go higher: in fact, the use case of Bitcoin as a currency contradicted its ability to go higher. Consumers don’t want to spend money whose value will go up: no one wants be the person who spent 10,000 bitcoin (currently worth over $1 billion) for two pizzas, and particularly for two pizzas from Papa John’s of all places4.

F—ing Bitcoin Keeps Going Up

So to skeptics, Bitcoin made no sense. It had no obvious quantitative value: it’s great that there is a fixed supply of 21 million bitcoins, but that means nothing without consistent demand for that 21 million. And the qualitative case simply didn’t have real support of history or even logic.

This became even worse as Bitcoin promoters slowly began to switch their arguments. Bitcoin’s early proponents called it out as a new currency, and this was the original intention. The original white paper is actually titled “Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System”. But since its utility as a currency never really got established — a few companies have accepted Bitcoin as payment, sometimes including Tesla, but no one has really cared — the bull case needed to change. And so Bitcoin steadily began to be pushed as “a store of value” — essentially, digital gold.

From the skeptics’ point of view, this only made things worse. Bitcoin and crypto have had 17 years to establish a real use case as a currency; outside of crime, it hasn’t arrived outside of very niche applications. And yet its supporters simply changed the rules — and, to add insult to injury, outperformed pretty much every single one of those traditional, fundamental-minded investors. The Bitcoin price is up more than 11x so far this decade to a price just shy of $110,000 as of this writing:

source: Koyfin

The Cost Of Bitcoin

For skeptics — to confess, myself included; somewhere on the Internet is an article where I argued investors should sell Bitcoin below $10,000 — none of this makes any sense. And that is all the more true because Bitcoin and crypto have a very real human cost5.

Scams cost crypto holders at least $10 billion in 2024, according to one estimate. Likely thousands of people have been trafficked to and imprisoned in centers in Southeast Asia that operate these frauds. And we now have another example of an apparently rising trend, in which large holders of crypto face terrifying violence in the real world:

A 37-year-old cryptocurrency investor was charged on Saturday with kidnapping a man and beating, shocking and torturing him for weeks inside a luxury townhouse in downtown Manhattan, all in a scheme to get the man’s Bitcoin password, the authorities said…

When the victim refused, the two men took him captive and subjected him to weeks of torture, which included beating him, shocking him with electric wires, hitting him with a gun and pointing the gun at his head. At one point, Mr. Woeltz and his accomplice carried the man to the top of the stairs in the five-story home, suspended him over the ledge and threatened to kill him if he did not give Mr. Woeltz his password, the complaint says.

In Paris this month, the daughter of the head of a French crypto exchange was nearly kidnapped, along with her toddler, in a brazen daytime attack. A Florida-based gang targeted victims — one of whom was 76 years old — across the country. Three teens from Florida kidnapped a Las Vegas man, drove him to the desert, and stole $4 million worth of crypto.

These are extreme forms of what is known as the “$5 wrench attack”, a term which comes from a 2009 XKCD cartoon:

source: XKCD

And it bears noting: there still is no apparent need for any of this. The value in Bitcoin — over $2 trillion as of this writing — seems disconnected from any sort of significant real-world application. The rise of ‘memecoins’, most famously the one issued by President Trump, boils this issue down to its purest form: these products are issued explicitly without any value (though apparently some people can get a dinner), and still find a buyer.

The GENIUS Act recently advanced through Congress establishes a framework for stablecoins — but no one has really explained how stablecoins themselves add value. They provide an on-ramp to the crypto world — turn a dollar into a stablecoin, trade the stablecoin for a crypto or use in a DeFi application, etc. — but it bears repeating: outside of price appreciation, that crypto world has not materially changed the lives of its users. There is still no real use case.

The Problem With ‘Trustless’

What we are doing is replicating the existing financial system on a ‘trustless’ basis. To supporters, this is precisely the point: a crypto-based financial system avoids the biases and whims of institutions and governments. It provides real freedom to its users.

But the spate of $5 wrench attacks itself proves a key point with broader implications for the political environment: trust is important. Trust matters. Institutions matter (a point crypto bulls suddenly, if implicitly, accept: they are cheering to ability to purchase stablecoins regulated by the U.S. government on Coinbase, an exchange worth $68 billion with heavy know-your-customer requirements). As an op-ed in the New York Times last week correctly noted, those stablecoins add significant potential risk to the existing financial system — in large part because of the conflict between a supposedly ‘trustless’ crypto world and an institutionalized system based on trust.

Without that trust, without those institutions, and without those guardrails, everything is actually worse. The freedom to send a stablecoin anywhere for you also means the unchecked ability of terrorists and criminals to do the same. No one in the developed world is at any risk of being kidnapped and tortured for their stock portfolio, because those portfolios are held by longstanding, trusted, institutions operating under a system that protects those portfolios6.

Yet, once again, it seems like the skeptics are wrong. Crypto is gaining acceptance in both parties (several Democrats voted to advance the GENIUS Act), the Bitcoin price is near an all-time high, and worldwide crypto in total is worth over $3 trillion. Incredibly, it’s still hard to clearly and concisely explain why any of those things are true.

Elon Heads Home

It seems like Elon Musk is done with government. As we wrote a month ago, the playbook he used to build investor confidence in Tesla did not build voter confidence in DOGE, or in Musk personally.

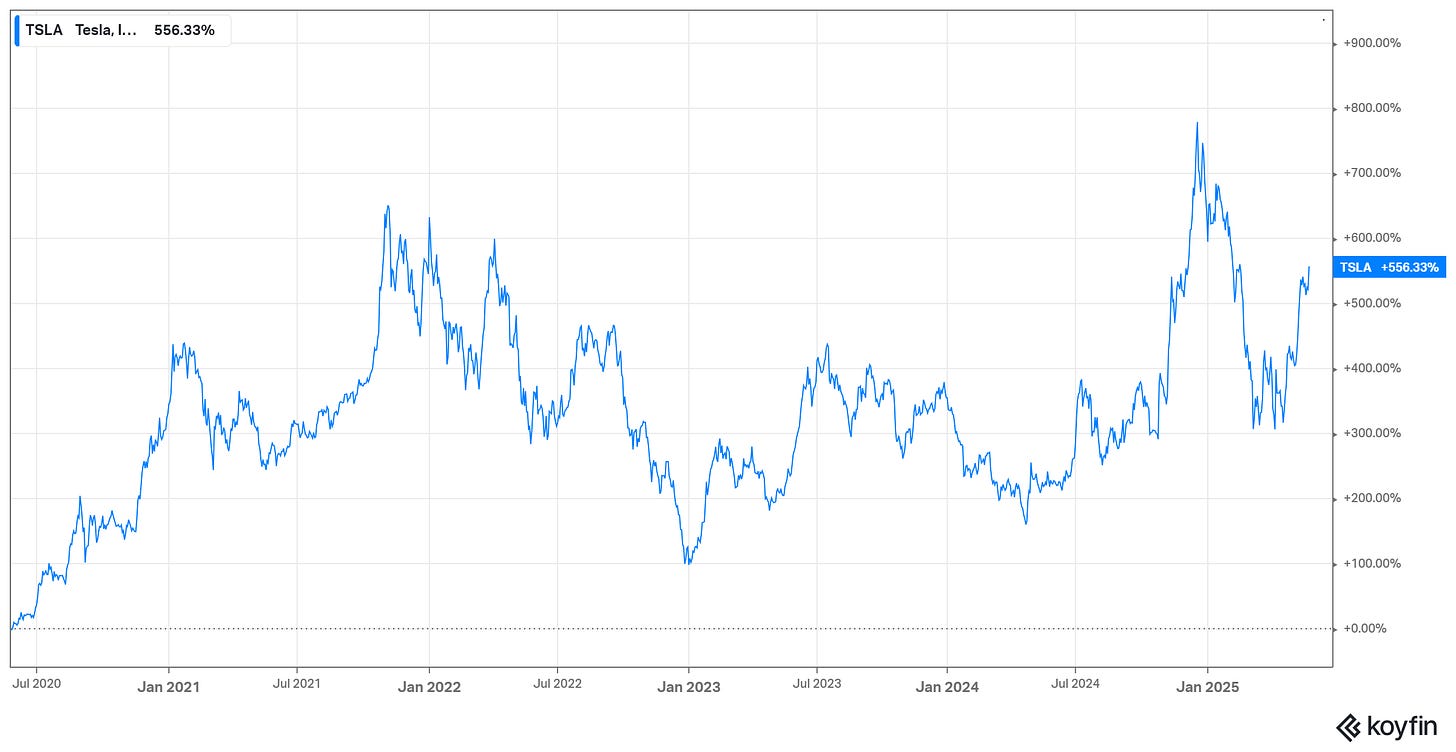

But much of the damage to Tesla, at least in terms of the stock price, has been undone:

source: Koyfin

The same seems true of Musk’s reputation on Wall Street, where investors seem relieved to have him back at Tesla, and in tech. Microsoft chief executive officer Satya Nadella and Musk had a friendly chat a Microsoft conference last week.

Given Musk’s admittedly incredible reach across industries, it seems likely that his involvement with DOGE will in a few years’ time be considered little more than a footnote. Even in a critical piece on Musk’s effective departure from government, The Atlantic positioned Musk as foiled not as much by personal failings as by the byzantine workings of the government and internal politics.

That is unfortunate, because Musk has done some damage:

Musk’s long history of overpromising and outright falsehoods at Tesla didn’t change the reputation of his company. At least with a portion of the American electorate, it has changed the reputation of the federal government.

The simple fact is that Musk repeatedly said things that were patently untrue. We’re always skeptical of the narratives that things “used to be different”: our government lied about Vietnam and the Iraq War, to name just two well-known examples of dishonesty. But those lies are well-known precisely because they were so blatant and so consequential, and it seems disappointing that Musk’s tales likely won’t resonate in the same way.

Musk, starting with his goal of $2 trillion in savings, which he kind-of-but-didn’t-really walk back in a contentious interview last weekend (and previously), aimed to convince the American public that government spending is a) massively titled toward waste and abuse and b) can be fixed solely through removing that waste. Neither is true, but Musk kept finding ways to insinuate it was without actually saying so. Plenty of Americans now believe him — which creates an impediment toward actually grappling with the nature and size of our debt and deficits, and having mature conversations about what should be prioritized.

To those of us who would like to see those mature conversations, Musk’s involvement has been incredibly frustrating. But then again, we don’t own any Tesla stock, either.

As of this writing, Vince Martin has no positions in any companies or securities mentioned — especially crypto.

If you enjoyed this piece, give us a ‘like’ to both steer future content and to help us spread the word. Thanks for reading!

The Internet bubble, for instance, was based on a very real societal change: the Internet did transform society. What investors got wrong (and more wrong in network infrastructure, where the losses were far greater than in actual ‘dot-com’ businesses) was the timing.

In real estate, the supposedly misrated AAA mortgage bonds that allegedly fueled the financial crisis actually performed roughly as the ratings agencies forecast; other factors (notably bank leverage) were far more important. We’ll no doubt go into more detail on this in the future.

To oversimplify, the amount of cash the business generates each year. Cash flow is not the same thing as profit, which is an accounting measure.

‘Cap rate’, short for ‘capitalization rate’ is net operating income divided by property value. If you buy a home for $250,000 and can make $25,000 in profit renting it out, your cap rate is 10%.

In case, you’re wondering, this actually happened, just over a decade ago.

On this point, we cannot recommend Number Go Up, by Bloomberg reporter Zeke Faux, highly enough. It is an absolutely gripping and often maddening read.

This is probably the point where we’re supposed to write “the current system has its problems, certainly, but…”. As far as custody of actual stocks goes, however, I mean, no, it doesn’t have any problems. An American with $50 can buy and sell thousands of stocks instantly, with full confidence in the execution of the trade and the safety of those assets.