WTF Is Going On: The Market View Of Trump's Tariffs

Calls for a "Trumpcession" look premature, while overseas trading suggests potential unintended consequences of a U.S-instigated trade war

Welcome to our first-ever post here at Wall Street And Main. Our structure will be as follows:

every Monday: WTF Is Going On. A review of some of the big recent stories, and (sometimes) a look ahead

every Wednesday: A deep dive into a big financial topic that impacts the world at large.

every Friday: WTF Happened. Basically Monday all over again, but hopefully with new topics.

We reserve the right to, at any point, change this schedule, structure, narratives, timing, opinions and font. On to the first piece.

Trump Tariffs Are Tanking The Economy…

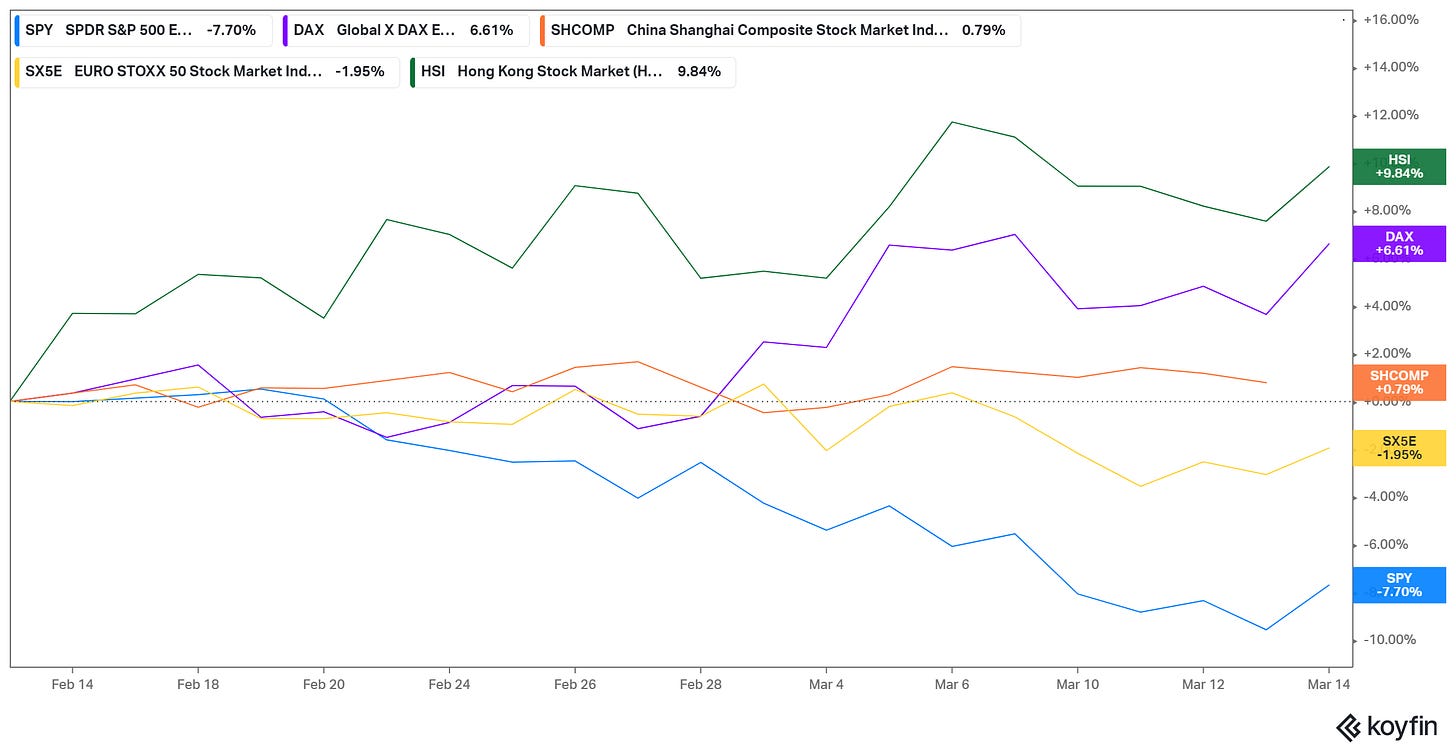

It seems exceptionally easy to argue that President Donald Trump’s tariff policies already are an economic disaster. The stock market has tumbled, with the Standard & Poor’s 500 (a list of mostly the 500 most valuable public companies1 in the U.S.) dropping 7.7% in a month:

source: Koyfin; total return of S&P 500 index fund (which includes dividend payments from included companies)

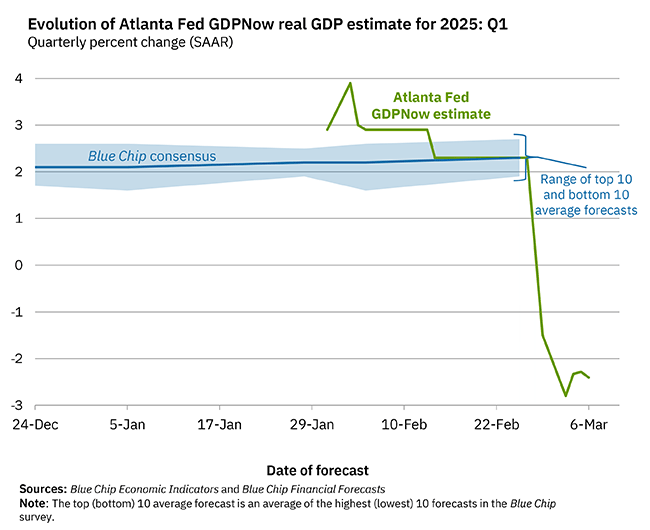

Not coincidentally, expectations for macroeconomic growth during the first quarter have plunged:

source: Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta

The pair of charts seem especially damaging because they represent both the near-term and, at least in theory, the long-term effects. The plunge in the GDPNow forecast isn’t coming because economists are quickly ratcheting down their expectations. In fact, the blue line, representing the Blue Chip consensus, is based on those economists, and it hasn’t moved.

Rather, GDPNow is based simply on a mathematical model that sources a range of inputs, including inflation figures, housing starts and sales, construction spending, automobile sales, and manufacturer sentiment surveys. And so the plunge in the model’s output is purely a sign that its inputs have gone to shit in a matter of weeks.

Meanwhile, the equity market is (again, in theory) long-term-oriented. A public company’s value should be equal to the sum of all of its future cash flows, discounted for time (a dollar in 2029 is worth less than one tomorrow). And so the nearly 8% decline in the S&P 500 reflects the fact that the total of all of the future earnings, not just those over the next quarter or year, of those 500 companies should be about 8% lower than investors projected a month ago2. Or, at the very least, it suggests that investors in aggregate believe that to be the case.

…Or Maybe Not

But if you wanted to push back against that case, you could on both fronts. The Atlanta Fed provides a spreadsheet detailing its model, and the inputs show that nearly all of the big plunge is being driven by import/export expectations:

source: Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta (author highlighting)

There is some noise in those figures, most likely due to stockpiling of imports (which in turn decreases the “net exports” figure) ahead of tariffs rather in direct response to those levies. Meanwhile, similar efforts from the Dallas and New York branches of the Fed aren’t anywhere near as pessimistic:

source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York

Even Trump Administration officials admit there’s going to be some turbulence if/when tariffs go ahead (more on this in a moment), but it’s not at all guaranteed that the near-term impact will be as extreme as the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow model currently suggests.

As for the equity market, there may be other factors at play beyond tariffs. The headlines look terrifying: at Thursday’s close, the S&P 500 alone had lost more than $5 trillion in market value in three weeks, meaning the U.S. market as a whole was down close to $7 trillion. (The S&P is about 80% of the total equity value of the U.S. market.)

But the U.S. market also added trillions in market value since Trump’s election, even though the actual election results were at least somewhat priced in (the 2024 results were much less of a surprise than those eight years earlier). The S&P is down 2% since Election Day and in context, this sell-off doesn’t look quite as big:

source: Koyfin; total return chart over one year

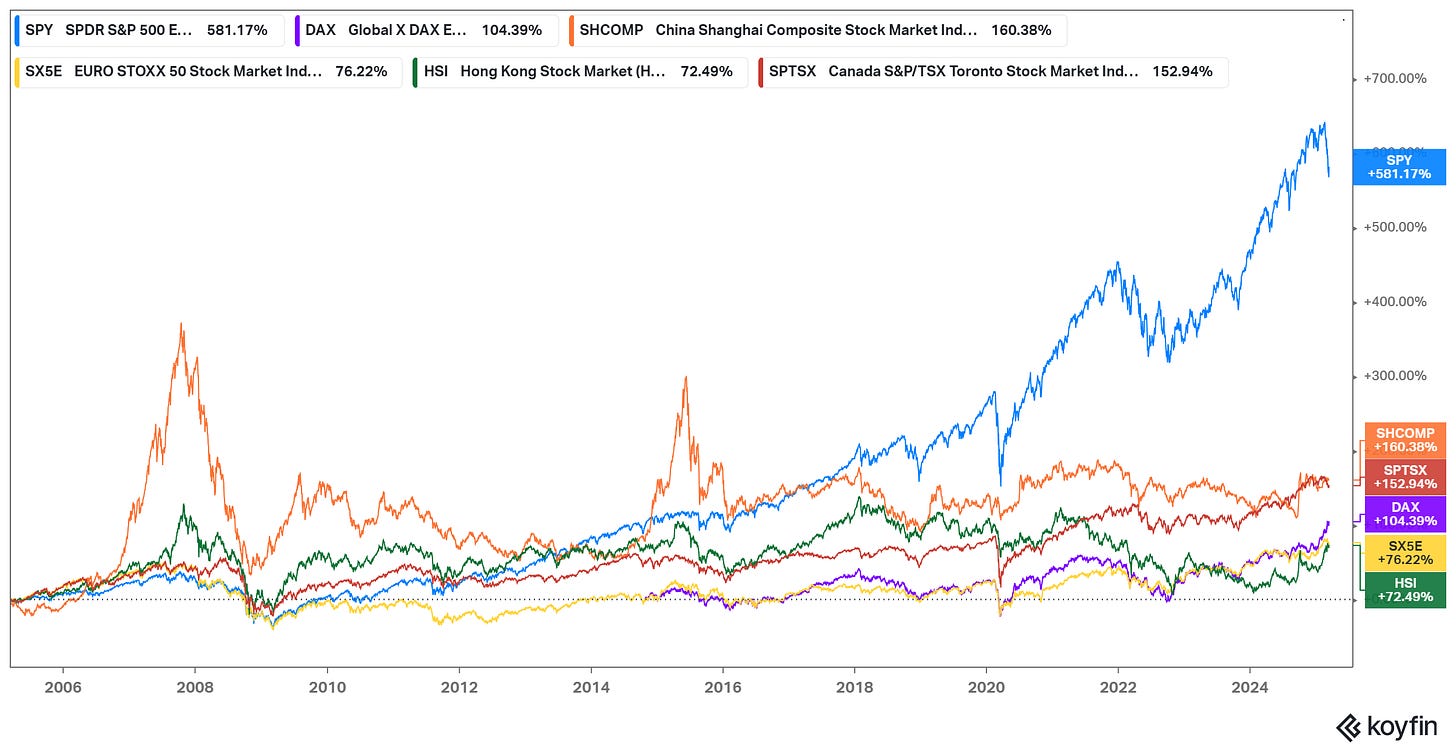

In a broader context, it barely seems worth a mention. Investors have handled much worse:

source: Koyfin; total return chart over 10 years

Indeed, a correction (the technical term for a decline of over 10% from the peak; a bear market occurs at a 20% drawdown) of some sort kind of made sense. And that correction has maybe been driven by factors beyond this Administration’s control.

After all, in 2023 we did see something close to a bubble in stocks that were beneficiaries of generative artificial intelligence. In addition, the so-called “Magnificent Seven” — Apple, Microsoft, Nvidia, Amazon, Alphabet (the owner of Google), Meta Platforms (owner of Facebook), and Tesla — gained a stunning 63% on average in 2024, accounting for over half of the gains in the S&P 500.

Both those popular and successful trades have reversed — as those kinds of trades often do. And while tariffs might have some impact on that move, there probably was some kind of correction due. Yes, the $5-6 trillion in market value lost in three weeks sounds like a lot. But in late January, the launch of DeepSeek, a genAI model from China, led to a one-day loss of nearly $1 trillion in just S&P 500 tech stocks.

In other words, shit happens. Tariffs are playing a role in trading — but they’re not the only factor. Pinning market movements on a single piece of external news is much like claiming a single extreme weather event proves (or dispels) the concept of climate change. Exceptionally complex systems do unexpected things for often unclear reasons.

The MAGA Nightmare?

To be fair, some readers might put more credence in the movement of the market — movement driven largely by thousands of professional, experienced, investors and traders — over the interpretation of a single writer.

And those readers might — as many do at the moment — see the market movement as a sign from investors that tariffs are prima facie a bad idea. The last round of tariffs, after all, led to the Great Depression (as seen in the Ben Stein clip from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off that is making the rounds on social media) — which impacted not just the U.S., but nearly every country in the world.

That historical interpretation is not quite accurate: tariffs exacerbated, but didn’t precipitate, the Great Depression. But at the moment, while the market seems to be projecting some level of pain for the U.S., it’s much more sanguine about the effects overseas:

source: Koyfin (one-month chart)

Over a month, Hong Kong stocks (the Hang Seng, or HSI in green) are up 10%, Germany (the DAX index in purple) is +6.6%, while China and European large caps are holding up.

There do seem to be expectations in the market that Trump’s policies can shock global and particularly European economies (with Germany perhaps having the most room for improvement) out of complacency. There’s plenty of room for that to happen. For example, Volkswagen, one of Germany’s largest companies, often has traded at a negative enterprise value; in other words, the value of the company is less than the value of its cash, investments, and a majority stake in Porsche.

A key reason is that the company’s employees (as well as the state of Lower Saxony, which owns 20% of shares) have such power that investors believe Volkswagen will lose money (lots of money) as its product lines shift from fossil fuels to electric vehicles. The nature of operating a European business (though VW certainly is an extreme example) is so complex that investors see this kind of transition as difficult, if not impossible. Chinese rivals in particular may outcompete VW, while regulators prevent the company from aggressively downsizing to, for instance, focus on a few profitable models.

But Trump’s tariffs can provide cover for a change in policies across the Continent, with environmental and labor concerns perhaps downgraded in favor of a focus on profitability and efficiency. In that event, Trump efforts could have a doubly negative effect: hurting American competitiveness overseas while sparking a turnaround in European industry. Clearly, there are some investors who believe that to be the case.

To be sure, here too a single month’s worth of market movement doesn’t tell the entire story. Stocks in Germany and Hong Kong have been rallying for some time, and the Canadian market has declined amid tariff drama. But these movements are a notable change from the multi-year trend — a trend that itself seems to undercut Trump’s claim that American companies are treated unfairly:

source: Koyfin (20-year chart)

American equities have absolutely dominated their overseas counterparts. Certainly, much of that growth has come from service providers and manufacturers whose products are made overseas (think Apple in China, for instance). Still, the idea that America is in decline or losing overall competitiveness is belied by the returns created by owning American companies versus their counterparts.

Changing the environment may change the trend. And, again, clearly some investors are betting on a long-term case that European companies can benefit from the effects of a trade war, if not the war itself. Certainly, European leadership has become vocal on the defense front, and in that context aggressive economic policy changes (in addition to reciprocal tariffs) wouldn’t be a surprise. And if Trump’s tariffs not only failed on their own merits, but improved global competitiveness in the process, that would be an economic issue for the U.S. and potentially a huge political drag for the Republicans as the midterms arrive in 2026.

Will Trump Go Forward? Or, When Politicians Listen To The Market

Of course, all this discussion is coming at a time when investors aren’t necessarily sure there will be trade wars, or even higher tariffs, at all. Trump already has been capricious: on Tuesday, he doubled metals tariffs on Canada, and then reversed course before the day was over.

And that fact perhaps adds more heft to the argument that recent equity market movements are material. After all, these movements are based on the possibility — 20%? 30%? 70%? — that Trump actually follows through.

A falling stock market will test his confidence, though for now both Trump and his surrogates insist that will not happen. But stock market sell-offs can motivate political responses. The most famous moment, perhaps, came in September 2008. Then, the House of Representatives somewhat surprisingly voted down a $700 billion bailout plan. Stocks fell 4% on the news, and kept falling. It took barely a week before a bailout of exactly the same size was passed. In eight days, 58 representatives changed their mind.

To be clear, this is not September 2008 — not yet. But the key question for investors, and the rest of us, is whether even moving in that direction will be enough to make Republican politicians, and Trump himself, lose their own nerve.

Disclosure: Vince Martin owns index funds that invest in the S&P 500. He does not have ownership in any companies mentioned in this article.

This isn’t entirely true; there are parameters around index inclusion that can leave out companies whose market capitalization (ie, the total value of all their shares at the current stock price) is high enough to make the index.

One example right now is Strategy, formerly known as MicroStrategy, which is the 127th-most valuable U.S.-domiciled company at the moment. Strategy, whose, er, strategy centers mostly on holding Bitcoin rather than running a business, needs to generate positive net income on a trailing four-quarter basis to be considered; mostly for vague accounting reasons, it hasn’t done so.

Again, in theory.