In Defense Of Corporations, Part II: The Shift Left And The New Gilded Age

Amid rising inequality, the rise in anti-corporate sentiment makes sense — but also misses the mark

PCU And The Left Of The 1990s

In the 1994 comedy PCU, a visiting high school senior — a ‘pre-frosh’, in the American parlance — visits the fictional Port Chester University. PCU — which obviously can also stand for “Politically Correct University” — is riven by various factions: vegans, ‘womynists’, environmentalists, black activists, even a group of underground fraternity members. As one character puts it, PCU is “a total P.C. war zone”, and the pre-frosh character manages, innocently and unintentionally, to upset pretty much every single combatant.

Despite a solid cast (David Spade, Jeremy Piven, Jessica Walter, and Jon Favreau, among others), PCU is a mostly forgettable movie. Its one contribution to pop culture is probably an ad-libbed line from Piven’s character: “You’re going to wear the shirt of the band you’re going to go see? Don’t be that guy.” But it did become a modest cult classic thanks to repeated airings on cable television, and it is a fairly accurate, if overheated, depiction of 1990s college culture.

PCU was written by a pair of alumni from Wesleyan University, a private liberal arts in Connecticut1. In the 1990s, Wesleyan was one of the most left-wing colleges in the country; it was pretty close to what modern right-wingers now believe every university is. As someone on campus at the time put it, the movie “might be a parody, but it’s barely an exaggeration.”

Indeed, the climactic scene — in which students exhausted by the constant discord protest against protests — was reportedly inspired by an actual event in the early 1990s. (There were more serious incidents as well: in 1990, the president’s office was firebombed by student activists.) And for someone who enrolled at Wesleyan a few years after the release of PCU, the environment depicted by the film is absolutely recognizable. Students then really did spell ‘womyn’ with a ‘y’ (so that it did not include the word ‘man’). The campus — students and faculty alike — was far to the left on nearly every issue. Sidewalks were constantly chalked with various social justice messages and efforts; protests weren’t quite as common (or aggressive) as earlier in the decade, but remained common enough.

But PCU misses one key aspect2 of the Wesleyan mindset in the late 1990s: an aggressively anti-corporate stance. My Economics 101 professor was a Communist; not in the sense that modern professors are attacked as such, but in the sense that he actually told us he was a Communist3. There were sporadic protests about sporadic U.S. military intervention overseas, which in my memory often included accusations that corporate interests (including oil companies, of course) had captured American foreign policy. On-campus environmentalists (“corporations rape the environment” seems to ring a bell) and anti-racists too saw big, U.S., business as the enemy.

At the time — and for years after — that perspective represented the fringe of even left-wing thought. ‘Third Way’ politics was at its zenith4, with an easy 1996 re-election win for U.S. president Bill Clinton and a landslide the next year for Tony Blair in the United Kingdom. Clinton’s vice president Al Gore didn’t invent the Internet — nor did he say he did — but he did work to procure aggressive public funding for private companies to build out its infrastructure. As a senator, Gore criticized corporations not for using their dominance to malign ends, but for not being aggressive enough in their use of computing power.

Even Barack Obama, the next Democratic president, was hardly anti-corporate. Despite constant (and mostly spurious) charges of socialism in his beliefs and his policies, he and his administration partnered with corporations for his signature bill. The Affordable Care Act of 2010 was modeled in part on a proposal originally developed by the conservative Heritage Foundation (though Heritage would later disavow its role), and required Americans to have health insurance procured from major insurers like UnitedHealthcare.

In the last decade, however, the attitude toward corporations has changed dramatically. Politicians like Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) have risen to prominence in part on the back of anti-corporate messages. Per Gallup, the percentage of Americans who are dissatisfied with the influence of major corporations is currently 72%, against 59% in 2015 and 48% as late as 2007. As we’ll discuss, not all of that change comes from the left, certainly, but even anecdotally it seems clear that the attitude among Democrats has changed.

Indeed, fourteen years after the ACA passed and entrenched large insurers at the center of U.S. healthcare, the chief executive officer of UnitedHealthcare was shot dead on the streets of Manhattan. More than a few who had been core supporters of Obama and his health care bill would cheer the murder, or at least defend its logic.

Why Anti-Corporatism Seems Obvious

In retrospect, the rise in anti-corporate sentiment seems not only understandable, but justified. The first big blow to corporate reputations this century probably arrived with the 2008-09 financial crisis. The narrative became that Wall Street had pushed America into recession (and millions of Americans out of their homes). That narrative was sometimes augmented by further claims that Wall Street knew the ostensible real estate bubble was bogus and then profited on the way down as well through “vulture investing” and other tactics.

The rise of the Tea Party on the right and Occupy Wall Street on the left both can be seen as a direct response to the crisis. Both clearly changed the political and policy structures of the two major parties. (Warren herself was first elected in 2012; in the primary season the year before, a businessman named Donald Trump led early polling for the Republican presidential nomination before deciding not to run.)

Meanwhile, since the crisis income inequality has continued to rise, becoming a significant issue on the left. Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century, published in 2013, had a material impact on the discourse around inequality. Even if the book seems almost forgotten now, its ideas clearly resonated, no doubt with some help from Sanders’s insurgent campaign in 2016. Piketty himself argued early that year that the rise of Sanders signaled “a new political era” in the U.S., one that would see the end of the “limitless glorification of the fortune amassed by rich white people.”

Broader cultural factors likely have contributed. As always, the Internet has played a role. That’s true in the specific sense that faceless, rich corporations are easy targets for the indignation that can often drive social media views — and in the broader belief that the Internet itself has become worse as corporate control has increased. In the classic and now widely-used formulation of Cory Doctorow, the “enshittification of the Internet” was driven by major corporations. (Doctorow specifically writes that Google built its massive market share by “cheating”; for instance, by paying off the likes of Apple to make its search engine the default.)

And in terms of both corporations and their owners, another intangible but obvious factor is influence. The richest person in the world in 1998 was Bill Gates, then the chief executive officer of Microsoft, which became the world’s most valuable company toward the end of that year. In the early days of the personal computer, both had their critics, certainly, (particularly Microsoft, whose products remained notoriously glitchy and which a few years later faced a massive, well-covered, antitrust suit) but neither were particularly polarizing. (Gates even did a 2001 cameo on Frasier as a fairly lovable, geeky, helpful guest; this of course was before he started putting microchips into vaccines5.)

But the likes of Walmart, Intel, and Coca-Cola didn’t have the reach or impact that modern corporations like Amazon, Facebook, Google, or modern Walmart do. Their CEOs and major shareholders weren’t part of the news cycle in the way that Elon Musk or Mark Zuckerberg or Jeff Bezos would be a quarter century later. Companies and billionaires weren’t entrenched within ‘culture wars’. Looking backwards, there’s a perception — one that is probably not entirely inaccurate — that corporations and their owners used to stay in their lane.

Finally, there’s just simply the sheer amount of dollars at the top. In 1998, per Forbes the world’s richest man was Microsoft’s Gates, at $51 billion. Only 19 people cracked the $10 billion mark. As I write this, Elon Musk is atop the list at Bloomberg6, at $366 billion. Gates’ $51 billion figure, adjusted for inflation, is just over $100 billion. The richest person in the world is ~3.6 times richer than his counterpart from just 27 years ago. The 50th-ranked person on the list is worth $37 billion (or ~$19 billion in 1998 dollars).

You can see this at the corporate level as well. At the end of 1999 (two-plus months before the dot-com bubble peaked), Microsoft was the world’s most valuable company, with a market capitalization of $419 billion, or ~$800 billion in current dollars. Last week, chipmaker Nvidia became the first company ever to reach a $4 trillion valuation. Adjusted for inflation, that’s about five times what Microsoft was worth just over a quarter century ago.

The New Gilded Age

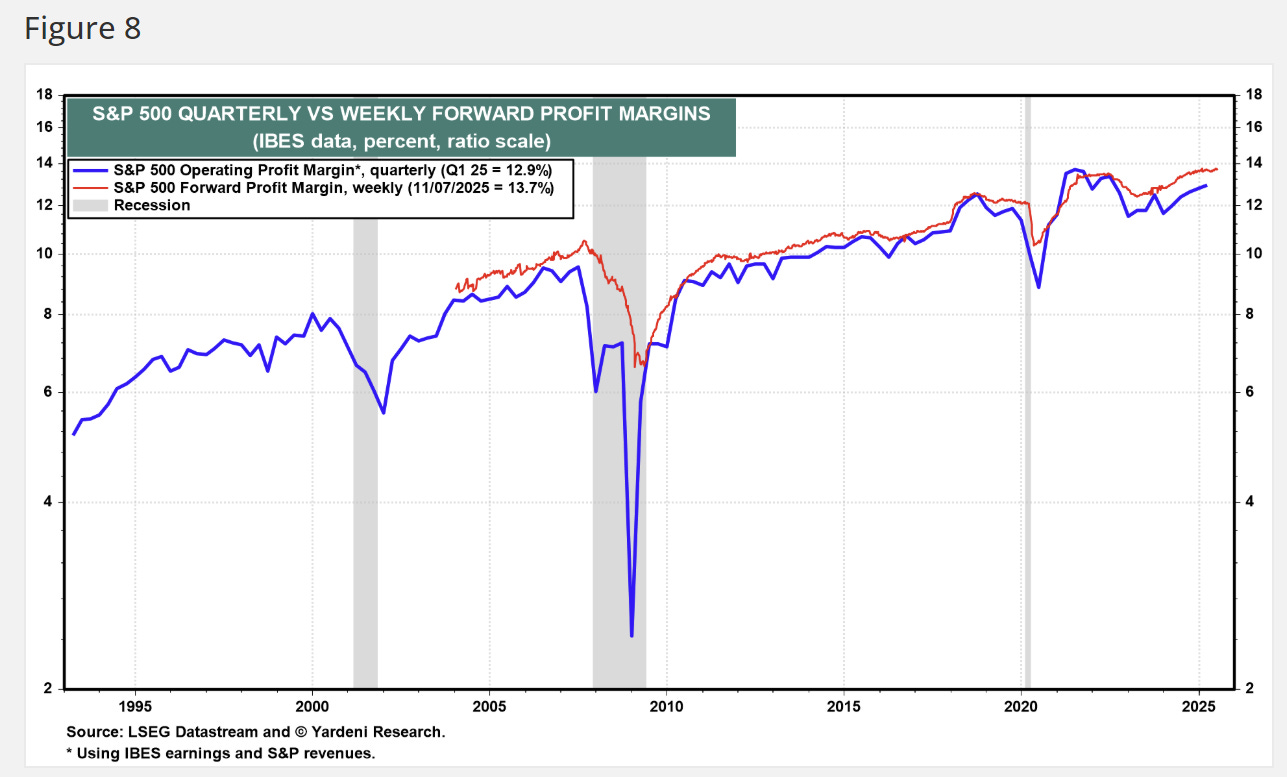

There’s just a lot more money at the top — in the stock market and with the one percent, or the 0.1 percent, or the 0.00001 percent — than there has been. And a simple chart might seem to explain why that is:

source: Yardeni Research

The line in blue is the operating profit margin of companies in the Standard & Poor’s 500 index7: essentially, how much profit (before interest expense on any debt and tax payments) corporations make on each dollar in revenue. Those margins are near an all-time high, and materially higher than they were last century (through the 1970s and 1980s, in fact, they were mostly in the 4% to 5% range, less than half the current total).

So the rich have more money, and more influence. Corporations are making more money (revenue for S&P 500 constituents obviously has grown as well, and at a rate faster than that of the economy as a whole). It’s thus clear that we live in a second Gilded Age — and to most (except, perhaps, the gilded themselves) that is not a good thing.

But a key question is: why are the rich so goddamn rich? There are some basic answers, including lower individual and corporate income taxes8. There’s the fact that wealth creates more wealth, particularly during a period when the U.S. stock market has soared (note that the bond market too had a multi-decade bull market). Within the cohorts of the very top, however, it’s worth considering that the typical boogeymen of the left — corruption, corporate concentration, lobbying, union-busting etc. — don’t actually appear to be the main factors.

Nor does the straight comparison to the first Gilded Age hold up. The leaders of that age were monopolists and often (always?) ruthless. Andrew Carnegie, reputedly the richest man in the world at the time, was a hard man who was not above using violence to break strikes and lower wages. The current richest man in the world looks like this:

source: New York Times

Tech Is The Problem (If It Is A Problem)

Indeed, if you look at what have become known as the “Magnificent Seven” — the seven most valuable companies in the world, which have driven a good chunk of recent gains in the U.S. stock market (over half of the index’s rally in 2024 came from just those seven stocks) — their rise doesn’t seem to be driven by antitrust violations, monopoly, government subsidies/protection, or necessarily evil or even unethical doings:

Nvidia simply makes far and away the best chips; supply has outweighed demand for years, giving the company incredible revenue growth ($27 billion in fiscal 2022, an estimated $200 billion this year) with huge pricing power.

Microsoft probably still has some antitrust concerns depending on one’s perspective (even if that case would be very different from what it was the first time around), but it faces competition in pretty much every end market and, for the most part, makes good products. The company’s cloud platform Azure, which accounts for a not-insignificant portion of its $3.8 trillion market capitalization, actually is not even number one in market share.

Apple faces no shortage of competition from Android products, yet still holds ~55% market share in the U.S. There are probably legitimate fairness/antitrust concerns about how it runs the App Store, but services (of which App Store is only a part) only account for ~25% of revenue, if likely a larger portion of overall profit.

Amazon has been a target of Warren among others for alleged anti-competitive behavior, and the subject of a Federal Trade Commission lawsuit filed in 2023. As with Apple, some of its behavior can be criticized, but it’s not solely a monopolist. Online retail is among the most competitive markets in history, and its Amazon Web Services platform (which leads Microsoft, Oracle, and others in market share) likely accounts for the majority of its $2.4 billion valuation.

Alphabet (formerly known as Google) did lose an FTC lawsuit this year (the company is appealing). It’s worth noting, however, that despite dominant market share in search, there are real worries that its near-monopoly is ending amid the rise of artificial intelligence tools like ChatGPT. It’s also worth noting that Alphabet has failed a lot outside of search, in hardware, with Google Plus, the Stadia cloud gaming service, etc.

Meta Platforms (formerly known as Facebook) too is facing an FTC suit over its acquisitions of Instagram in 2012 and WhatsApp in 2014. But as even the judge in the case has noted, the key question is how to define the industry; for instance, is TikTok (not necessarily a networking site) a legitimate competitor to Meta’s various offerings? The driver of Facebook’s growth, meanwhile, clearly was network effects: most online markets become “winner-take-most” and, in the case of social media, usually “winner-takes-all”, with Twitter/X being another example.

Tesla (here in 2025 no longer one of the top seven, having been passed by chipmakers Broadcom and Taiwan Semiconductor) prospered in an electric vehicle market where few thought it would win, and — whatever one’s opinion of Musk — simply makes better cars than its rivals. Legacy U.S. automakers went heavy into EVs in the post-pandemic period, and yet Tesla still holds nearly 50% share of the U.S. market. Investors believe that Musk and his company will have similar success in autonomous driving and robotaxis, and are valuing Tesla accordingly.

To be sure, for most of these companies (and other U.S. giants) reasonable observers can point to behavior that is or should be anti-competitive. Those with more expansive views of the effects of corporate power — such as European regulators or the Biden FTC under Lina Khan (her appointment being a clear example of the shift away from “Third Way” politics) — might point to the deleterious effects on producers and/or argue that the pure focus of U.S. law on consumers misses broader societal effects.

But the argument that “unfair” behavior by corporations is the key driver of inequality and greater wealth at the top simply doesn’t hold up. The primary reason U.S. corporations are more profitable is because more of them are in tech: tech is now about 30% of the S&P 500 in terms of valuation, against a single-digit percentage in the 1970s. And tech companies simply are more profitable than other kinds of firms: producing software or websites (or ‘fabless’ chips, in which another company actually manufactures the end product) has much higher margins than producing goods. Once product dominance is secured, the incremental cost of another software subscriber or another website visitor is pretty close to zero, which means revenue growth drives exponential increases in profit; this is obviously not true for rolled steel or automobiles.

And in most cases, at least in terms of the core product (whether it’s Google Search or an Nvidia chip), that product dominance was secured (mostly) fairly. These companies by and large are making the best products. (And for those on the left who decry the impact of corporate consolidation on labor, it’s worth noting that the overcompensation and breezy life of most white-collar workers for the likes of Google has become an online trope.)

To be sure, this does not mean that everything is fine, that Big Tech / big business is pure, or that public policy can’t redress the effects of concentrated wealth. It doesn’t necessarily mean that Meta or Alphabet, for instance, shouldn’t be broken up. There are fair, grounded arguments that such a concentration of wealth is a net negative for society, and that policy around taxation, antitrust and labor should adapt in response.

But those arguments need to incorporate the fact that a big driver of increasingly concentrated wealth is the structural change in the U.S. economy created by the rise of technology. Meta is perhaps the most extreme example of this.

What Do You Do With Meta?

Take the following facts. Mark Zuckerberg is the third-richest person in the world ($247 billion). In 2023, Facebook had 272 million monthly active users in the US and Canada. Across all platforms, Meta earned $227 per each one of those users (the company no longer discloses this metric, which is why we’re using slightly dated figures).

Put another way, the average US & Canada Facebook user ‘paid’ Meta something like $2009 in 2023, if not in cash then in some form of attention (is advertising consumption a currency?). That revenue comes in part because of the company’s stunning dominance: there are probably a little over 300 million adults in those two countries combined. Adding in older teens, in the U.S. and Canada likely over 80% of the eligible population visits a Meta site every month. And that figure of course is so high precisely because 80% of the eligible population visits those sites. Facebook is the perfect example of network effects, in which the growth of the network improves the attractiveness of the network, which drives growth, which makes the network more attractive, etc. etc. As a result, Meta generated $62 billion in net profit in 2024, and that includes a nearly $18 billion loss in its Reality Labs business, which is developing virtual/augmented reality.

So if you believe (as I suspect many do) that no one ‘should’ have a fortune of $247 billion and/or the concentration of power that Meta and Zuckerberg do, then, what, exactly, do you think should be done here? One could sharply increase income taxes in the top bracket, but that doesn’t really make much difference here: about $240 billion of Zuckerberg’s fortune is held in Meta stock.

To tackle that wealth, the government could start taxing unrealized gains, as a budget proposal last year proposed. But there are a lot of unintended consequences there, among them a probable need to issue refunds when markets go down. (We’d also note that under that policy it’s pretty unlikely Elon Musk would still be at Tesla, or even necessarily have joined it in its infancy; for those on the left that might be a plus, given his politics, or a minus, given that Tesla unquestionably has moved electric vehicles closer to the mainstream.) And even at the proposed ~45% tax rate under the Biden/Harris proposal, Zuckerberg would still be worth ~$140 billion; that’s not really a huge step toward there being no billionaires.

Now, you could instead focus on the business. If you’re worried about individual power, you can ban the dual-stock structure, which enables Zuckerberg to control Meta’s voting power (and thus its board of directors and broader strategy) even without majority ownership of common shares. But in a founder-driven era, even a Zuckerberg without technical control would be driving strategy.

You could argue, as did the Khan FTC, that Instagram and WhatsApp should be separated, or that what was then still called Facebook shouldn’t have been allowed to purchase either platform in the first place. But that doesn’t necessarily fix the core problem of wealth and power concentration: presumably, Instagram’s founders and/or its supporting venture capitalists would have captured the benefits that accrued instead to Meta shareholders and Zuckerberg. Splitting up Meta now means the company still is largely owned by the same economic class; it’s not like shares of WhatsApp will be distributed to the underprivileged or deposited in the federal treasury.

And what can you possibly do about competition and pricing? Any remedies here are incredibly anti-capitalist, and boil down to basically limiting Meta’s pricing or forcing users elsewhere to limit the dominance of its platforms.

Again, Meta is an extreme example of the broader effect of tech business models, but the issues here are only slightly exaggerated version of those that dominate the sector more broadly. If a software company can serve an incremental subscriber for a modest cost, either it (and its shareholders) are going to make huge profits, or the government has to somehow restrict pricing. If Amazon and Walmart are hoovering market share through economies of scale and the ease of online shopping, regulators have to get uncomfortably involved in day-to-day operations to reverse those trends.

Again, there are arguments that those more aggressive remedies now are required. But the simple case that big companies, Big Tech, and big wealth are stealing from the lower classes, or (as we discussed in part one) driving inflation through greed, simply ignore the reality of the new economy.

The most valuable companies in the 21st century are not akin to those that dominated the U.S. economy toward the end of the 19th. They are not ‘price gouging’ (Amazon and Walmart unquestionably have pushed down prices; Google and Facebook don’t have to directly cost any money at all). And they are not aggressively crushing labor power and wages in the pursuit of market share. Say what you will about Mark Zuckerberg, he never sent the Pinkertons anywhere.

As of this writing, Vince Martin has no direct positions in any companies or securities mentioned. He does own index funds which include ownership of companies mentioned here.

If you enjoyed this piece, give us a ‘like’ to both steer future content and to help us spread the word. Thanks for reading!

There are many more U.S. colleges with ‘Wesleyan’ in the name; this is the original Wesleyan, so to speak.

As far as I can tell based on my own memory and reading reviews and the screenplay; the movie no longer airs anywhere due to an apparent rights issue.

It’s hard to put into words how shocking that was to hear as a 17-year-old in 1996. The Commies were the bad guys! All the movies said so. And, of course, they had just lost what felt like the biggest, most important war in history without a direct shot fired. It was like hearing a geology professor argue the Earth was flat.

In retrospect, a lot of things feel like they were at their zenith then. The late 1990s really were kind of great.

It’s a joke, I swear.

Adding to the sense of influence and reach around these massive fortunes, the Forbes list came out every year. The Bloomberg list is updated daily.

As we’ve noted before, the S&P 500 is basically the 500 most valuable companies listed on U.S. exchanges; that’s not the precise definition, but close enough for our purposes.

We will cover corporate taxes in detail at some point in the future, because the issue of which people actually pay corporate taxes is a complex and interesting one. But given that wealthier people have proportionately greater ownership in publicly- and privately-held businesses, it does stand to reason that lower corporate taxes disproportionately benefit that class in turn.

Some of that $227 comes from Instagram and WhatsApp, but Meta has said a strong majority is from the Facebook platform; $200 is a reasonable and helpfully round estimate.