WTF Is Going On: Horseshoe Theory, Shareholder Proposals And Walmart

Walmart faces the effects of the right wing's economic U-turn — again

Political Activists Get Activist

In theory, the management of a corporation is answerable to its ultimate owners: the shareholders. Those shareholders are represented by the board of directors, who can express their broader preferences to the managers who actually run the day-to-day operations.

In practice, for publicly traded corporations, the structure can be a little messier. The chief executive officer (ie, the top manager) often is also the chairman (ie, the head of the board). Directors communicate with managers often; with most shareholders not at all. Particularly in the common structure in which no one has anything close to majority ownership, shareholders aren’t quite as in charge as the legal structure of a corporation might suggest.

But there are mechanisms by which shareholders — even small shareholders — can let their feelings be known. The most important is the annual meeting. Shareholders are given the opportunity to vote on the directors; if frustrated, they can nominate new directors and/or vote current directors out. (One of the more well-known efforts on this front came in 2021, when a then-unknown hedge fund called Engine No. 1 put three directors on the board of ExxonMobil with the goal of pushing the company to reduce its carbon footprint. Other funds, known as activist funds, use this strategy to overhaul companies in more traditional, financially-focused ways, such as selling parts of the business or replacing underperforming management.) There are votes (though non-binding votes) on how and how much managers are compensated, and on the independent accounting firm used to audit the company’s financial results.

Shareholders can also contact the board to propose the board take a certain action. There are a number of rules around this process, and in some cases the company can disregard the shareholder (most notably if the proposal is batshit insane). But there is a path toward putting matters up for a vote by the entire shareholder base at the annual meeting. In recent years, political activists have begun to use this method to argue for structural changes at major companies.

The 2025 Shareholder Proposals At Walmart

One of the more popular targets has been Walmart. This is hardly surprising: the company is the largest retailer in the U.S. Its size — annual revenue is over 2% of U.S. gross domestic product — is such that its decisions literally can alter the global supply chain.

And so, ahead of the company’s 2025 annual meeting, a number of organizations bought Walmart shares1 in the hopes of forcing votes on proposals that might change the giant’s broader policies. The exact number of proposals submitted is not disclosed, but it was likely quite high; in the proxy statement filed ahead of the meeting, Walmart’s board made its thoughts on shareholder proposals quite clear [emphasis ours]:

While occasional reasonable and good-faith proposals are submitted and sometimes adopted, this is the exception. Proponents often include interest groups seeking to leverage Walmart's name recognition to draw attention to themselves or advocate for a cause, regardless of Walmart's performance on the issue. In some cases, they hold just enough shares to pass the ownership threshold required to submit a proposal. Many proposals attempt to force Walmart to take sides on sensitive or polarizing issues, which would erode—rather than enhance—shareholder value.

This year’s batch is no exception: We received competing proposals seeking to draw us into taking sides on polarizing social issues, proposals that would interfere with our judgment about which products to carry and how to engage our customers, proposals that rehash issues already recently rejected by shareholders, and proposals that would require us to make statements that could be used against us in litigation.

But in 2025, seven proposals did make it through:

A request for Walmart to get a third-party assessment of its policies regarding requests for information by law enforcement around customer prescriptions. The proposal notes a potential conflict between state and federal laws “regarding certain medications related to contraception, abortion, and gender-affirming treatments”; the implication is thus that Walmart needs to protect the consumers being prescribed those treatments from more aggressive government policies.

A request for a report on the company’s ability to increase its sustainable packaging efforts. (Again, a shareholder proposal can’t tell a company how to actually run its business, and so reports that highlight the issue are requested as a first step; if the report then says, “yeah, we have like no sustainable packaging at all,” that in turn can drive media attention and potentially lawsuits that hopefully will push the company in the desired direction.)

A request for the board to re-examine its policies around plastics, filed by the conservative National Legal and Policy Center. The NLPC is basically asking for more plastics; its supporting statement claims that “Plastic pollution is primarily the result of poor disposal practices, not production.”

A request for a third-party “independent racial equity audit”.

A request for yet another report, this one on why Walmart took so long to reverse its DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion) initiatives, citing changes made in November after apparent negotiations with right-wing influencer Robby Starbuck

A request for a report on workplace health and safety efforts.

A request for a report on the company’s discrimination against buyers and sellers of advertising, discrimination allegedly enabled by Walmart’s work with GARM (Global Alliance for Responsible Media), an organization that aimed to tackle disinformation and hate speech.

The board opposed all seven proposals (which makes one wonder about the quality of the ones that didn’t even make it through to a shareholder vote). But what is notable here is the number of right-leaning proposals: three of the seven clearly seek to move the company in a more conservative direction.

The Rise Of Right-Wing Shareholder Activism

Indeed, Walmart’s own history is a microcosm of how these proposals have evolved as political tools. In 2015, Walmart’s proxy statement had one political proposal: a request for a report on greenhouse gas emissions from international marine shipping of the company’s goods. Four years later, there were four, all on stereotypical left-wing issues (the effects of single-use plastic bags, a report on the use of antibiotics by suppliers, a proposed policy to include hourly workers as potential members of the board of directors, and a report on strengthening the prevention of sexual harassment in the workplace).

In the late 2010s, these proposals were used almost exclusively by those pushing more typically liberal/progressive causes, often around workers’ rights, racial equity, and even foreign policy. One group of Benedictine nuns in Texas has been pushing Walmart for years to improve its treatment of workers; the group appears to have owned stock for at least two decades. They are part of a surprisingly large number of religious orders involved in activist investing. Another order successfully pushed for Walmart to stop selling adult video games; four others submitted repeated proposals at gunmaker Smith & Wesson before filing a stockholder lawsuit. Benedictine nuns in Kansas have filed over 350 shareholder proposals at dozens of companies, including a resolution that opposed Halliburton’s contracts for the Iraq War.

This decade, however, the story has changed. As The Conference Board has noted, DEI proposals have peaked, while ‘anti-DEI’ proposals have soared2:

source: The Conference Board

This is not necessarily a surprise. The rise in shareholder activism by the right simply mirrors the rise in activism in the right more generally. As recently as Trump’s first term, the GOP was largely dominated by a conservative, free-market ideology; it made little sense for any member or supporter of the party to target for-profit corporations (and particularly Walmart). The first major act of Trump’s first term, after all, included a substantial corporate tax cut.

The perspective of the right largely was that public companies should try and make as much money as possible; Milton Friedman’s famous 1970 article, “The Social Responsibility of Business Is To Increase Its Profits”, still held sway. Consumers, regulators, and elected politicians were supposed to determine whether, say, plastic packaging was damaging. Corporate executives were supposed to drive profit growth — and since, as we’ve discussed previously, those executives were fabulously compensated for doing precisely that, there was little reason for conservatives to get involved in the operations of those businesses.

To be sure, those supporting anti-DEI and other right-leaning proposals would argue that their underlying ideology hasn’t necessarily changed. In this telling, the move by conservatives into shareholder activism is simply a response to dramatic overreach by their counterparts on the left-wing — and a few too many ‘woke’ leaders in corporate boardrooms that are driving destructive DEI and ESG policies.

That may be true. But it is still striking to see the right adopt a tool used by the left for decades. And it is even more striking to see right-wing activists target Walmart, of all companies.

Trump Turns Left And Hits Walmart

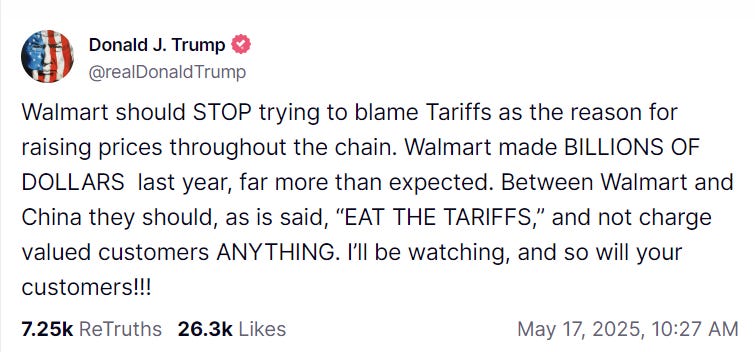

On that note:

Much has been made about President Trump’s claim that Walmart (along with China) should “EAT THE TARIFFS” — ostensibly an admission that his previous claims that China alone pays the tariffs was false. But that bridge seemingly already had been crossed multiple times, notably in the comment that kids “might have two dolls instead of 30”.

What is more striking is Trump’s claim that Walmart is making “billions of dollars”, as if that is a reason for the company to simply swallow the impact of tariffs. Here, too, the right is emulating the left:

Last year, Walmart made $10 billion in profit and paid its CEO over $20 million in compensation, and it has authorized $20 billion in stock buybacks, which will benefit its wealthiest stockholders…[As a result], Walmart can afford to pay its employees a living wage of at least $15 per hour.

That quote comes from Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT), who (thanks to yet another shareholder proposal) was actually speaking in person at Walmart’s general meeting back in 2019.

Sanders of course is not the only person on the left to make a similar claim: that Walmart, because of its profits, can spread the largesse to its employees. It can, perhaps, “eat the wages”, to use Trump’s formulation. A decade earlier, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) invited Walmart employees to Congress as part of a bid to raise the federal minimum wage.

It’s wild how similar the language is among Sanders, Warren (who noted the wealth of the founding Walton family as well as Walmart’s overall profits) and Trump. And it is stunning —in fact, it is dumbfounding — to see a Republican President of the United States attack Walmart for making too much money.

Yes, the attack is perhaps a way for Trump to obscure the real-life impact of his trade policies. But the fact that the attack might work with his base — who almost certainly disproportionately shop at Walmart — is a signal of how far right-wing ideology has shifted in just a few years.

In early April, after new tariffs were announced on “Liberation Day”, we argued that the nature of the tariffs “seems to confirm that Trumpism in fact is simply the mirror image of modern progressivism…The difference, from the perspective of Trump and his supporters, is who the victims are.”

Trump’s criticism of Walmart is yet another piece of evidence for that argument, and the broader “horseshoe theory” that the left and right wings of U.S. politics are starting to coalesce on certain issues.

Walmart’s Profit Margins

Beyond the irony of Donald Trump sounding like Bernie Sanders is another irony: the fact that both men fail to understand exactly how much money Walmart actually makes — and how it makes that money.

The billions of dollars in profit (operating income, which covers the cost of goods as well as all operating expenses, was over $29 billion in fiscal 2025) likely sounds to both the right and left as a massive pool of profit that can alternately hike wages or ‘eat’ tariffs. But relative to the massive revenue base, operating profit honestly is not that high: it was 4.3% of revenue in fiscal 2025. Competitors are higher, but not that much higher. In 2024, Amazon’s retail business in North America generated 6.4% margins (its cloud business much more profitable); Target 5.2%; national grocer Kroger barely 3%.

A material wage hike would eat up much of those profits. A 2024 shareholder proposal suggested that Walmart move to offering a living wage, which it cited in 2022 as $25 per hour3. In its response, Walmart said its average wage for hourly associates was over $17.50; in supply chain, the figure jumps to over $26.

It’s not clear exactly how many hourly associates Walmart has; the company has 1.6 million employees in the U.S., and a large majority presumably are in-store associates. If the hourly base is 1 million, assuming a 30-hour week, a $7.50 per hour raise would cost more than $11 billion — nearly 40% of the company’s operating profit.

The tariff math is even worse. It’s not clear exactly how much of its product Walmart imports from China (the company does not specify the figure in its financial reports). Reuters reported in late 2023 that China accounted for 60% of Walmart imports, based on bill of lading figures, though the company called that figure based on a “partial picture”. Walmart says on its website that two-thirds of U.S. merchandise was “made, grown, or assembled domestically”. But that broad category could include items that originated in China — and merchandise is not necessarily reflective of revenue. (Heads of lettuce are likely supplied domestically; 4K televisions are not.)

But even assuming Walmart splits the current 30% tariffs — and Chinese suppliers, which run on exceptionally low margins themselves, cannot afford that — if ~30% of revenue comes from Chinese imports, then Walmart’s operating profit is gone.

It seems likely that 30% is probably in the ballpark of what China’s share actually is — which is why Walmart does plan to raise prices. The company said as much on last week’s conference call following its first quarter earnings — and it was that statement that led to Trump’s broadside on Saturday morning.

Low, Low Prices

And it’s worth noting just how fundamentally opposed Walmart management is to raising prices at all. As the excellent 2006 book The Wal-Mart Effect points out, the company’s mantra of “low, low prices” is not just an advertising slogan, but essentially Walmart’s reason for being. Author Charles Fishman wrote then that “Wal-Mart4 managers convey a sense not just of challenge and achievement, but also of being on a mission: Delivering low prices is worthwhile, it changes the lives of customers.”

Both Doug McMillon, the current chief executive officer, and John Furner, CEO of Walmart U.S.5 are lifers; each started as an hourly associate in the 1980s. They are immersed in that culture, which still exists: Fishman writes of Walmart executive offices that are furnished with customer samples, to save money (and keep prices low); a close friend who worked with the company reported not that long ago that the same sourcing strategy still exists.

As Fishman and many others have noted, that relentless focus may well have a cost. Economists are still debating the net effect that Walmart has on its communities, but common sense suggests there is some downside. The company can put pressure on local suppliers or remove those suppliers altogether. Wages may come down. There is a more qualitative impact as well: it doesn’t take too long traveling rural/exurban parts of the U.S. to see a town with a gleaming, massive Walmart located just a couple of miles from an empty, or emptying, downtown.

The conservative argument for the chain was long that the focus on prices benefited everyone. In the National Review in late 2017, Kevin D. Williamson (only somewhat) tongue-in-cheek compared a Walmart to the Taj Mahal and Mount Rushmore, telling readers to “spare a thought for the everyday miracle of the Walmart Super Center, which contains within its walls a selection of worldly riches and exotic treasures that Cleopatra would have blushed to contemplate.” Yes, there were secondary costs — but everything has a cost, and it was up to local communities to decide whether Walmart should have a presence, and to consumers themselves to understand whether those secondary costs were worth paying.

But as with so much else in the second Trump term, that vision of conservatism has been all but discarded. This is an activist, interventionist government seeking to remake the economy and permanently alter the social fabric. In that context, it’s little wonder that President Trump and Senator Sanders sound so much alike.

As of this writing, Vince Martin has no positions in any companies or securities mentioned.

If you enjoyed this piece, give us a ‘like’ to both steer future content and to help us spread the word. Thanks for reading!

Again, you don’t have to be a major shareholder: to file a proposal, an investor can own as little as $2,000 of the stock if held for three years.

The Russell 3000 includes, basically, the 3,000 biggest public companies in the U.S., roughly three-quarters of the total number.

Interestingly, the proposal was couched in financial terms rather than as a moral appeal. The proposal argued that the “gain in Company profit that comes at the expense of society and the economy is a bad trade for Company shareholders who are diversified and rely on broad economic growth to achieve their financial objectives.”

In other words, with the rise of index investing, in which investors own, say, the 500 companies in the Standard & Poor’s 500 index, companies should have a broader social eye. This actually is part of the financial case for ESG investing that conservatives sometimes ignore in favor of seeing a purely political movement.

The company legally changed its name from “Wal-Mart Stores” to “Walmart” in early 2018.

Almost 20% of Walmart’s revenue comes from outside the U.S.